Musical Theory on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of

Pitch is the lowness or highness of a tone, for example the difference between

Pitch is the lowness or highness of a tone, for example the difference between

Notes can be arranged in a variety of scales and

Notes can be arranged in a variety of scales and

Rhythm is produced by the sequential arrangement of sounds and silences in time.

Rhythm is produced by the sequential arrangement of sounds and silences in time.

A

A

A chord, in music, is any

A chord, in music, is any

Timbre, sometimes called "color", or "tone color," is the principal phenomenon that allows us to distinguish one instrument from another when both play at the same pitch and volume, a quality of a voice or instrument often described in terms like bright, dull, shrill, etc. It is of considerable interest in music theory, especially because it is one component of music that has as yet, no standardized nomenclature. It has been called "... the psychoacoustician's multidimensional waste-basket category for everything that cannot be labeled pitch or loudness," but can be accurately described and analyzed by

Timbre, sometimes called "color", or "tone color," is the principal phenomenon that allows us to distinguish one instrument from another when both play at the same pitch and volume, a quality of a voice or instrument often described in terms like bright, dull, shrill, etc. It is of considerable interest in music theory, especially because it is one component of music that has as yet, no standardized nomenclature. It has been called "... the psychoacoustician's multidimensional waste-basket category for everything that cannot be labeled pitch or loudness," but can be accurately described and analyzed by

In music, " dynamics" normally refers to variations of intensity or volume, as may be measured by physicists and audio engineers in

In music, " dynamics" normally refers to variations of intensity or volume, as may be measured by physicists and audio engineers in

Articulation is the way the performer sounds notes. For example, ''

Articulation is the way the performer sounds notes. For example, ''

In music, texture is how the

In music, texture is how the

The term musical form (or musical architecture) refers to the overall structure or plan of a piece of music, and it describes the layout of a composition as divided into sections. In the tenth edition of ''

The term musical form (or musical architecture) refers to the overall structure or plan of a piece of music, and it describes the layout of a composition as divided into sections. In the tenth edition of ''

Musical expression is the art of playing or singing music with emotional communication. The elements of music that comprise expression include dynamic indications, such as forte or piano, phrasing, differing qualities of timbre and articulation, color, intensity, energy and excitement. All of these devices can be incorporated by the performer. A performer aims to elicit responses of sympathetic feeling in the audience, and to excite, calm or otherwise sway the audience's physical and emotional responses. Musical expression is sometimes thought to be produced by a combination of other parameters, and sometimes described as a transcendent quality that is more than the sum of measurable quantities such as pitch or duration.

Expression on instruments can be closely related to the role of the breath in singing, and the voice's natural ability to express feelings, sentiment and deep emotions. Whether these can somehow be categorized is perhaps the realm of academics, who view expression as an element of musical performance that embodies a consistently recognizable

Musical expression is the art of playing or singing music with emotional communication. The elements of music that comprise expression include dynamic indications, such as forte or piano, phrasing, differing qualities of timbre and articulation, color, intensity, energy and excitement. All of these devices can be incorporated by the performer. A performer aims to elicit responses of sympathetic feeling in the audience, and to excite, calm or otherwise sway the audience's physical and emotional responses. Musical expression is sometimes thought to be produced by a combination of other parameters, and sometimes described as a transcendent quality that is more than the sum of measurable quantities such as pitch or duration.

Expression on instruments can be closely related to the role of the breath in singing, and the voice's natural ability to express feelings, sentiment and deep emotions. Whether these can somehow be categorized is perhaps the realm of academics, who view expression as an element of musical performance that embodies a consistently recognizable

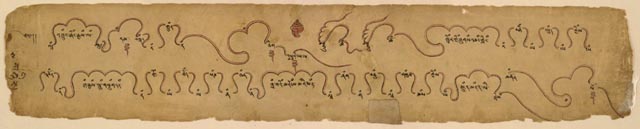

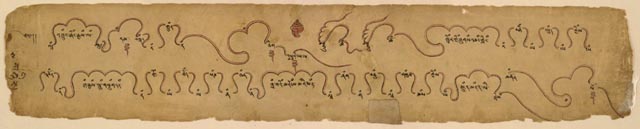

Musical notation is the written or symbolized representation of music. This is most often achieved by the use of commonly understood graphic symbols and written verbal instructions and their abbreviations. There are many systems of music notation from different cultures and different ages. Traditional Western notation evolved during the Middle Ages and remains an area of experimentation and innovation.In the 2000s, computer

Musical notation is the written or symbolized representation of music. This is most often achieved by the use of commonly understood graphic symbols and written verbal instructions and their abbreviations. There are many systems of music notation from different cultures and different ages. Traditional Western notation evolved during the Middle Ages and remains an area of experimentation and innovation.In the 2000s, computer

Musical analysis is the attempt to answer the question ''how does this music work?'' The method employed to answer this question, and indeed exactly what is meant by the question, differs from analyst to analyst, and according to the purpose of the analysis. According to

Musical analysis is the attempt to answer the question ''how does this music work?'' The method employed to answer this question, and indeed exactly what is meant by the question, differs from analyst to analyst, and according to the purpose of the analysis. According to

A music genre is a conventional category that identifies some pieces of music as belonging to a shared tradition or set of conventions. It is to be distinguished from ''musical form'' and ''musical style'', although in practice these terms are sometimes used interchangeably.

Music can be divided into different genres in many different ways. The artistic nature of music means that these classifications are often subjective and controversial, and some genres may overlap. There are even varying academic definitions of the term ''genre ''itself. In his book ''Form in Tonal Music'', Douglass M. Green distinguishes between genre and Musical form, form. He lists madrigal (music), madrigal, motet, canzona, ricercar, and dance as examples of genres from the Renaissance music, Renaissance period. To further clarify the meaning of ''genre'', Green writes, "Beethoven's Op. 61 and Mendelssohn's Op. 64 are identical in genre—both are violin concertos—but different in form. However, Mozart's Rondo for Piano, K. 511, and the ''Agnus Dei'' from his Mass, K. 317 are quite different in genre but happen to be similar in form." Some, like Peter van der Merwe (musicologist), Peter van der Merwe, treat the terms ''genre'' and ''style'' as the same, saying that ''genre'' should be defined as pieces of music that came from the same style or "basic musical language."

Others, such as Allan F. Moore, state that ''genre'' and ''style'' are two separate terms, and that secondary characteristics such as subject matter can also differentiate between genres. A music genre or subgenre may also be defined by the musical techniques, the style, the cultural context, and the content and spirit of the themes. Geographical origin is sometimes used to identify a music genre, though a single geographical category will often include a wide variety of subgenres. Timothy Laurie argues that "since the early 1980s, genre has graduated from being a subset of popular music studies to being an almost ubiquitous framework for constituting and evaluating musical research objects".

Musical technique is the ability of musical instrument, instrumental and vocal musicians to exert optimal control of their instruments or vocal cords to produce precise musical effects. Improving technique generally entails practicing exercises that improve muscular sensitivity and agility. To improve technique, musicians often practice fundamental patterns of notes such as the Natural minor, natural, Minor scale, minor, Major scale, major, and

A music genre is a conventional category that identifies some pieces of music as belonging to a shared tradition or set of conventions. It is to be distinguished from ''musical form'' and ''musical style'', although in practice these terms are sometimes used interchangeably.

Music can be divided into different genres in many different ways. The artistic nature of music means that these classifications are often subjective and controversial, and some genres may overlap. There are even varying academic definitions of the term ''genre ''itself. In his book ''Form in Tonal Music'', Douglass M. Green distinguishes between genre and Musical form, form. He lists madrigal (music), madrigal, motet, canzona, ricercar, and dance as examples of genres from the Renaissance music, Renaissance period. To further clarify the meaning of ''genre'', Green writes, "Beethoven's Op. 61 and Mendelssohn's Op. 64 are identical in genre—both are violin concertos—but different in form. However, Mozart's Rondo for Piano, K. 511, and the ''Agnus Dei'' from his Mass, K. 317 are quite different in genre but happen to be similar in form." Some, like Peter van der Merwe (musicologist), Peter van der Merwe, treat the terms ''genre'' and ''style'' as the same, saying that ''genre'' should be defined as pieces of music that came from the same style or "basic musical language."

Others, such as Allan F. Moore, state that ''genre'' and ''style'' are two separate terms, and that secondary characteristics such as subject matter can also differentiate between genres. A music genre or subgenre may also be defined by the musical techniques, the style, the cultural context, and the content and spirit of the themes. Geographical origin is sometimes used to identify a music genre, though a single geographical category will often include a wide variety of subgenres. Timothy Laurie argues that "since the early 1980s, genre has graduated from being a subset of popular music studies to being an almost ubiquitous framework for constituting and evaluating musical research objects".

Musical technique is the ability of musical instrument, instrumental and vocal musicians to exert optimal control of their instruments or vocal cords to produce precise musical effects. Improving technique generally entails practicing exercises that improve muscular sensitivity and agility. To improve technique, musicians often practice fundamental patterns of notes such as the Natural minor, natural, Minor scale, minor, Major scale, major, and

In the modern era, musical set theory uses the language of mathematical set theory in an elementary way to organize musical objects and describe their relationships. To analyze the structure of a piece of (typically atonal) music using musical set theory, one usually starts with a set of tones, which could form motives or chords. By applying simple operations such as transposition (music), transposition and Melodic inversion, inversion, one can discover deep structures in the music. Operations such as transposition and inversion are called isometries because they preserve the intervals between tones in a set. Expanding on the methods of musical set theory, some theorists have used abstract algebra to analyze music. For example, the pitch classes in an equally tempered octave form an abelian group with 12 elements. It is possible to describe just intonation in terms of a free abelian group.

In the modern era, musical set theory uses the language of mathematical set theory in an elementary way to organize musical objects and describe their relationships. To analyze the structure of a piece of (typically atonal) music using musical set theory, one usually starts with a set of tones, which could form motives or chords. By applying simple operations such as transposition (music), transposition and Melodic inversion, inversion, one can discover deep structures in the music. Operations such as transposition and inversion are called isometries because they preserve the intervals between tones in a set. Expanding on the methods of musical set theory, some theorists have used abstract algebra to analyze music. For example, the pitch classes in an equally tempered octave form an abelian group with 12 elements. It is possible to describe just intonation in terms of a free abelian group.

In music theory, serialism is a method or technique of

In music theory, serialism is a method or technique of

Music semiology (semiotics) is the study of signs as they pertain to music on a variety of levels. Following Roman Jakobson, Kofi Agawu adopts the idea of musical semiosis being introversive or extroversive—that is, musical signs within a text and without. "Topics," or various musical conventions (such as horn calls, dance forms, and styles), have been treated suggestively by Agawu, among others. The notion of Musical Gestures, gesture is beginning to play a large role in musico-semiotic enquiry.

:"There are strong arguments that music inhabits a semiological realm which, on both ontogenetic and phylogenetic levels, has developmental priority over verbal language."

Writers on music semiology include Kofi Agawu (on topical theory,

Music semiology (semiotics) is the study of signs as they pertain to music on a variety of levels. Following Roman Jakobson, Kofi Agawu adopts the idea of musical semiosis being introversive or extroversive—that is, musical signs within a text and without. "Topics," or various musical conventions (such as horn calls, dance forms, and styles), have been treated suggestively by Agawu, among others. The notion of Musical Gestures, gesture is beginning to play a large role in musico-semiotic enquiry.

:"There are strong arguments that music inhabits a semiological realm which, on both ontogenetic and phylogenetic levels, has developmental priority over verbal language."

Writers on music semiology include Kofi Agawu (on topical theory,

Music theory in the practical sense has been a part of education at conservatories and music schools for centuries, but the status music theory currently has within academic institutions is relatively recent. In the 1970s, few universities had dedicated music theory programs, many music theorists had been trained as composers or historians, and there was a belief among theorists that the teaching of music theory was inadequate and that the subject was not properly recognised as a scholarly discipline in its own right. A growing number of scholars began promoting the idea that music theory should be taught by theorists, rather than composers, performers or music historians. This led to the founding of the Society for Music Theory in the United States in 1977. In Europe, the French ''Société d'Analyse musicale'' was founded in 1985. It called the First European Conference of Music Analysis for 1989, which resulted in the foundation of the ''Société belge d'Analyse musicale'' in Belgium and the ''Gruppo analisi e teoria musicale'' in Italy the same year, the ''Society for Music Analysis'' in the UK in 1991, the ''Vereniging voor Muziektheorie'' in the Netherlands in 1999 and the ''Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie'' in Germany in 2000. They were later followed by the Russian Society for Music Theory in 2013, the Polish Society for Music Analysis in 2015 and the ''Sociedad de Análisis y Teoría Musical'' in Spain in 2020, and others are in construction. These societies coordinate the publication of music theory scholarship and support the professional development of music theory researchers.

As part of their initial training, music theorists will typically complete a B.Mus or a Bachelor of Arts, B.A. in music (or a related field) and in many cases an M.A. in music theory. Some individuals apply directly from a bachelor's degree to a PhD, and in these cases, they may not receive an M.A. In the 2010s, given the increasingly interdisciplinary nature of university graduate programs, some applicants for music theory PhD programs may have academic training both in music and outside of music (e.g., a student may apply with a B.Mus and a Masters in Music Composition or Philosophy of Music).

Most music theorists work as instructors, lecturers or professors in colleges, universities or Music school, conservatories. The job market for tenure-track professor positions is very competitive: with an average of around 25 tenure-track positions advertised per year in the past decade, 80–100 PhD graduates are produced each year (according to the Survey of Earned Doctorates) who compete not only with each other for those positions but with job seekers that received PhD's in previous years who are still searching for a tenure-track job. Applicants must hold a completed PhD or the equivalent degree (or expect to receive one within a year of being hired—called an "ABD", for "All But Dissertation" stage) and (for more senior positions) have a strong record of publishing in peer-reviewed journals. Some PhD-holding music theorists are only able to find insecure positions as sessional lecturers. The job tasks of a music theorist are the same as those of a professor in any other humanities discipline: teaching undergraduate and/or graduate classes in this area of specialization and, in many cases some general courses (such as Music appreciation or Introduction to Music Theory), conducting research in this area of expertise, publishing research articles in peer-reviewed journals, authoring book chapters, books or textbooks, traveling to conferences to present papers and learn about research in the field, and, if the program includes a graduate school, supervising M.A. and PhD students and giving them guidance on the preparation of their theses and dissertations. Some music theory professors may take on senior administrative positions in their institution, such as Dean (education), Dean or Chair of the School of Music.

Music theory in the practical sense has been a part of education at conservatories and music schools for centuries, but the status music theory currently has within academic institutions is relatively recent. In the 1970s, few universities had dedicated music theory programs, many music theorists had been trained as composers or historians, and there was a belief among theorists that the teaching of music theory was inadequate and that the subject was not properly recognised as a scholarly discipline in its own right. A growing number of scholars began promoting the idea that music theory should be taught by theorists, rather than composers, performers or music historians. This led to the founding of the Society for Music Theory in the United States in 1977. In Europe, the French ''Société d'Analyse musicale'' was founded in 1985. It called the First European Conference of Music Analysis for 1989, which resulted in the foundation of the ''Société belge d'Analyse musicale'' in Belgium and the ''Gruppo analisi e teoria musicale'' in Italy the same year, the ''Society for Music Analysis'' in the UK in 1991, the ''Vereniging voor Muziektheorie'' in the Netherlands in 1999 and the ''Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie'' in Germany in 2000. They were later followed by the Russian Society for Music Theory in 2013, the Polish Society for Music Analysis in 2015 and the ''Sociedad de Análisis y Teoría Musical'' in Spain in 2020, and others are in construction. These societies coordinate the publication of music theory scholarship and support the professional development of music theory researchers.

As part of their initial training, music theorists will typically complete a B.Mus or a Bachelor of Arts, B.A. in music (or a related field) and in many cases an M.A. in music theory. Some individuals apply directly from a bachelor's degree to a PhD, and in these cases, they may not receive an M.A. In the 2010s, given the increasingly interdisciplinary nature of university graduate programs, some applicants for music theory PhD programs may have academic training both in music and outside of music (e.g., a student may apply with a B.Mus and a Masters in Music Composition or Philosophy of Music).

Most music theorists work as instructors, lecturers or professors in colleges, universities or Music school, conservatories. The job market for tenure-track professor positions is very competitive: with an average of around 25 tenure-track positions advertised per year in the past decade, 80–100 PhD graduates are produced each year (according to the Survey of Earned Doctorates) who compete not only with each other for those positions but with job seekers that received PhD's in previous years who are still searching for a tenure-track job. Applicants must hold a completed PhD or the equivalent degree (or expect to receive one within a year of being hired—called an "ABD", for "All But Dissertation" stage) and (for more senior positions) have a strong record of publishing in peer-reviewed journals. Some PhD-holding music theorists are only able to find insecure positions as sessional lecturers. The job tasks of a music theorist are the same as those of a professor in any other humanities discipline: teaching undergraduate and/or graduate classes in this area of specialization and, in many cases some general courses (such as Music appreciation or Introduction to Music Theory), conducting research in this area of expertise, publishing research articles in peer-reviewed journals, authoring book chapters, books or textbooks, traveling to conferences to present papers and learn about research in the field, and, if the program includes a graduate school, supervising M.A. and PhD students and giving them guidance on the preparation of their theses and dissertations. Some music theory professors may take on senior administrative positions in their institution, such as Dean (education), Dean or Chair of the School of Music.

Job: Adjunct/Affiliate in Music Theory

Philadelphia: St Josephs University. * Anon. (2014).

Full-time, Tenure-track Position in Music Theory, at the Rank of Assistant Professor, Beginning Fall 2014

. Buffalo: University at Buffalo Department of Music. * Anon. (2015).

College of William and Mary: Assistant Professor of Music, Theory and Composition (Tenure Eligible)

. Job Listings, MTO (accessed 10 August 2015). * Willi Apel, Apel, Willi, and Ralph T. Daniel (1960). ''The Harvard Brief Dictionary of Music''. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc. *

Archaeological Evidence for the Emergence of Language, Symbolism, and Music – An Alternative Multidisciplinary Perspective

. ''Journal of World Prehistory'' 17, no. 1 (March): 1–70. * Despopoulos, Agamemnon, and Stefan Silbernagl (2003). ''Color Atlas of Physiology'', fifth edition. New York and Stuttgart: Thieme. . * * Dunbar, Brian (2010). ''Practical Music Theory: A Guide to Music as Art, Language, and Life''. Rochester, MN: Factum Musicae. . * * Haas, Shady R., and J. W. Creamer (2001).

Dating Caral, a Pre-ceramic Site in the Supe Valley on the Central Coast of Peru

. ''Science (journal), Science'' 292: 723–726. . * Harnsberger, Lindsey C. (1997). "Articulation". ''Essential Dictionary of Music: Definitions, Composers, Theory, Instrument and Vocal Ranges'', second edition. The Essential Dictionary Series. Los Angeles: Alfred Publishing. . * Hewitt, Michael (2008). ''Music Theory for Computer Musicians''. United States: Cengage Learning. . * Houtsma, Adrianus J. M. (1995).

Pitch Perception

. In ''Hearing'', Handbook of Perception and Cognition Volume 2, second edition, edited by Brian C. J. Moore, 267–295. San Diego and London. Academic Press. . * Huang, Xiang-peng (黄翔鹏) (1989). "Wuyang Jiahu gudi de ceyin yanjiu (舞阳贾湖骨笛的测音研究)" [Pitch Measurement Studies of Bone Flutes from Jiahu of Wuyang County]. ''Wenwu'' (文物) [Cultural Relics], no. 1:15–17. Reprinted in 黄翔鹏文存 [Collected Essays of Huang Xiang-Peng], 2 vols, edited by Zhongguo Yishu Yanjiuyuan Yinyue Yanjiusuo (中国艺术研究院音乐研究所), 557–560. Ji'nan, China: Shandong Wenyi Chubanshe, 2007. . * Hung, Eric (2012).

Western University, Don Wright Faculty of Music: Tenure-Track Appointment in Music Theory

. Toronto: MusCan. * Ray Jackendoff, Jackendoff, Ray and

Text at archive.org

* Miguel, Roig-Francoli (2011). ''Harmony in Context'', Second edition, McGraw-Hill Higher Education. . * Mirelman, Sam, and Theo Krispijn (2009). "The Old Babylonian Tuning Text UET VI/3 899". ''Iraq'' 71:43–52. * Nave, R. (n.d.).

, Hyperphysics website, Georgia State University (accessed 5 December 2014). * Steve Olson, Olson, Steve (2011).

A Grand Unified Theory of Music

. ''Princeton Alumni Weekly'' 111, no. 7 (9 February) (Online edition accessed 25 September 2012). * * Owen, Harold (2000). ''Music Theory Resource Book''. Oxford University Press. . *

''Psychology of Music''

New York, London: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. * * Sorce, Richard (1995). ''Music Theory for the Music Professional''. [N.p.]: Ardsley House. . * Stevens, S. S., J. Volkmann, and E. B. Newman (1937). "A Scale for the Measurement of the Psychological Magnitude Pitch". ''Journal of the Acoustical Society of America'' 8, no. 3:185–190. * Richard Taruskin, Taruskin, Richard (2009). ''Music from the Earliest Notations to the Sixteenth Century: The Oxford History of Western Music.'' Oxford University Press . * Taylor, Eric (1989). ''AB Guide to Music Theory, Part 1''. London: Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music. . * Taylor, Eric (1991). ''AB Guide to Music Theory, Part 2''. London: Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music. . * Thrasher, Alan (2000). ''Chinese Musical Instruments''. London and New York: Oxford University Press. . * Hugh Tracey, Tracey, Hugh (1969). "The Mbira Class of African Instruments in Rhodesia". ''African Music Society Journal'' 4, no. 3:78–95. * Dmitri Tymoczko, Tymoczko, Dmitri (2011). ''A Geometry of Music: Harmony and Counterpoint in the Extended Common Practice''. Oxford Studies in Music Theory. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. . * Martin Litchfield West, West, Martin Litchfield (1994). "The Babylonian Musical Notation and the Hurrian Melodic Texts". ''Music & Letters'' 75, no. 2 (May): 161–179 * Wu, Zhao (吴钊) (1991). "Jiahu guiling gudi yu Zhongguo yinyue wenming zhi yuan (贾湖龟铃骨笛与中国音乐文明之源)" [The relation of Jiahu bone flutes and turtle shell shakers to the origin of Chinese music]. ''Wenwu'' (文物) [Cultural Relics], no. 3: 50–55. * Wu, Zhongzian, and Karin Taylor Wu (2014). ''Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches: Tian Gan Dizhi, The Heart of Chinese Wisdom Traditions''. London and Philadelphia: Singing Dragon (Jessica Kingsley Publishers). * Yamaguchi, Masaya (2006). ''The Complete Thesaurus of Musical Scales'', revised edition. New York: Masaya Music Services. . * Zhang, Juzhong; Garman Harboolt, Cahngsui Wang, and Zhaochen Kong (1999).

Oldest Playable Musical Instrument Found at Jiahu Early Neolithic Site in China

. ''Nature (journal), Nature'' (23 September): 366–368. * * Zhang, Juzhong, and L. K. Kuem (2005). "The Magic Flutes". ''Natural History (magazine), Natural History'' 114:43–49 * Zhang, Juzhong, X. Xiao, and Y. K. Lee (2004). "The Early Development of Music: Analysis of the Jiahu Bone Flutes". ''Antiquity (journal), Antiquity'' 78, no. 302:769–779

Music theory resources

* Oscar van Dillen, Dillen, Oscar van

Outline of basic music theory

(2011)

Why A Little Bit of Theory Matters

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Music Theory Music theory, Music history Musicology

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspect ...

. ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory". The first is the "rudiments

In ''rudimental drumming'', a form of percussion music, a drum rudiment is one of a number of relatively small patterns which form the foundation for more extended and complex drumming patterns. The term "drum rudiment" is most closely assoc ...

", that are needed to understand music notation (key signatures, time signatures, and rhythmic notation); the second is learning scholars' views on music from antiquity to the present; the third is a sub-topic of musicology

Musicology (from Greek μουσική ''mousikē'' 'music' and -λογια ''-logia'', 'domain of study') is the scholarly analysis and research-based study of music. Musicology departments traditionally belong to the humanities, although some mu ...

that "seeks to define processes and general principles in music". The musicological approach to theory differs from music analysis "in that it takes as its starting-point not the individual work or performance but the fundamental materials from which it is built."

Music theory is frequently concerned with describing how musicians and composers make music, including tuning systems and composition methods among other topics. Because of the ever-expanding conception of what constitutes music, a more inclusive definition could be the consideration of any sonic phenomena, including silence. This is not an absolute guideline, however; for example, the study of "music" in the ''Quadrivium

From the time of Plato through the Middle Ages, the ''quadrivium'' (plural: quadrivia) was a grouping of four subjects or arts—arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy—that formed a second curricular stage following preparatory work in the ...

'' liberal arts university curriculum, that was common in medieval Europe, was an abstract system of proportions that was carefully studied at a distance from actual musical practice. But this medieval discipline became the basis for tuning systems in later centuries and is generally included in modern scholarship on the history of music theory.

Music theory as a practical discipline encompasses the methods and concepts that composers and other musicians use in creating and performing music. The development, preservation, and transmission of music theory in this sense may be found in oral and written music-making traditions, musical instruments

A musical instrument is a device created or adapted to make musical sounds. In principle, any object that produces sound can be considered a musical instrument—it is through purpose that the object becomes a musical instrument. A person who pl ...

, and other artifacts. For example, ancient instruments from prehistoric sites around the world reveal details about the music they produced and potentially something of the musical theory that might have been used by their makers. In ancient and living cultures around the world, the deep and long roots of music theory are visible in instruments, oral traditions, and current music-making. Many cultures have also considered music theory in more formal ways such as written treatises and music notation. Practical and scholarly traditions overlap, as many practical treatises about music place themselves within a tradition of other treatises, which are cited regularly just as scholarly writing

Academic writing or scholarly writing is nonfiction produced as part of academic work, including reports on empirical Field research, fieldwork or research in facilities for the natural sciences or social sciences, monographs in which scholars a ...

cites earlier research.

In modern academia, music theory is a subfield of musicology

Musicology (from Greek μουσική ''mousikē'' 'music' and -λογια ''-logia'', 'domain of study') is the scholarly analysis and research-based study of music. Musicology departments traditionally belong to the humanities, although some mu ...

, the wider study of musical cultures and history. Etymologically, ''music theory'', is an act of contemplation of music, from the Greek word θεωρία, meaning a looking at, a viewing; a contemplation, speculation, theory; a sight, a spectacle. As such, it is often concerned with abstract musical aspects such as tuning and tonal systems, scales, consonance and dissonance, and rhythmic relationships. In addition, there is also a body of theory concerning practical aspects, such as the creation or the performance of music, orchestration, ornamentation, improvisation, and electronic sound production. A person who researches or teaches music theory is a music theorist. University study, typically to the MA or PhD level, is required to teach as a tenure-track music theorist in a US or Canadian university. Methods of analysis include mathematics, graphic analysis, and especially analysis enabled by western music notation. Comparative, descriptive, statistical, and other methods are also used. Music theory textbooks, especially in the United States of America, often include elements of musical acoustics Musical acoustics or music acoustics is a multidisciplinary field that combines knowledge from physics, psychophysics, organology (classification of the instruments), physiology, music theory, ethnomusicology, signal processing and instrument buil ...

, considerations of musical notation

Music notation or musical notation is any system used to visually represent aurally perceived music played with instruments or sung by the human voice through the use of written, printed, or otherwise-produced symbols, including notation fo ...

, and techniques of tonal composition

Composition or Compositions may refer to:

Arts and literature

*Composition (dance), practice and teaching of choreography

*Composition (language), in literature and rhetoric, producing a work in spoken tradition and written discourse, to include v ...

(harmony

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. However ...

and counterpoint

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tradi ...

), among other topics.

History

Prehistory

Preserved prehistoric instruments, artifacts, and later depictions of performance in artworks can give clues to the structure of pitch systems in prehistoric cultures. See for instancePaleolithic flutes

During regular archaeological excavations, several flutes that date to the European Upper Paleolithic were discovered in caves in the Swabian Alb region of Germany. Dated and tested independently by two laboratories, in England and Germany, the a ...

, Gǔdí, and Anasazi flute

The Anasazi flute is the name of a prehistoric end-blown flute replicated today from findings at a massive cave in Prayer Rock Valley in Arizona, United States by an archaeological expedition led by Earl H. Morris in 1931. The team excavated 15 ca ...

.

Antiquity

Mesopotamia

Several surviving Sumerian and Akkadian clay tablets include musical information of a theoretical nature, mainly lists of intervals and tunings. The scholar Sam Mirelman reports that the earliest of these texts dates from before 1500 BCE, a millennium earlier than surviving evidence from any other culture of comparable musical thought. Further, "All the Mesopotamian texts bout musicare united by the use of a terminology for music that, according to the approximate dating of the texts, was in use for over 1,000 years."China

Much of Chinese music history and theory remains unclear. Chinese theory starts from numbers, the main musical numbers being twelve, five and eight. Twelve refers to the number of pitches on which the scales can be constructed. TheLüshi chunqiu

The ''Lüshi Chunqiu'', also known in English as ''Master Lü's Spring and Autumn Annals'', is an encyclopedic Chinese classic text compiled around 239 BC under the patronage of the Qin Dynasty Chancellor Lü Buwei. In the evaluation of Michae ...

from about 239 BCE recalls the legend of Ling Lun. On order of the Yellow Emperor, Ling Lun collected twelve bamboo lengths with thick and even nodes. Blowing on one of these like a pipe, he found its sound agreeable and named it ''huangzhong'', the "Yellow Bell." He then heard phoenixes singing. The male and female phoenix each sang six tones. Ling Lun cut his bamboo pipes to match the pitches of the phoenixes, producing twelve pitch pipes in two sets: six from the male phoenix and six from the female: these were called the ''lülü'' or later the ''shierlü''.

Apart from technical and structural aspects, ancient Chinese music theory also discusses topics such as the nature and functions of music. The ''Yueji'' ("Record of music", c1st and 2nd centuries BCE), for example, manifests Confucian moral theories of understanding music in its social context. Studied and implemented by Confucian scholar-officials .. these theories helped form a musical Confucianism that overshadowed but did not erase rival approaches. These include the assertion of Mozi (c. 468 – c. 376 BCE) that music wasted human and material resources, and Laozi's claim that the greatest music had no sounds. ..Even the music of the ''qin'' zither, a genre closely affiliated with Confucian scholar-officials, includes many works with Daoist references, such as ''Tianfeng huanpei'' ("Heavenly Breeze and Sounds of Jade Pendants").

India

TheSamaveda

The Samaveda (, from ' "song" and ' "knowledge"), is the Veda of melodies and chants. It is an ancient Vedic Sanskrit text, and part of the scriptures of Hinduism. One of the four Vedas, it is a liturgical text which consists of 1,875 verses. A ...

and Yajurveda

The ''Yajurveda'' ( sa, यजुर्वेद, ', from ' meaning "worship", and ''veda'' meaning "knowledge") is the Veda primarily of prose mantras for worship rituals.Michael Witzel (2003), "Vedas and Upaniṣads", in ''The Blackwell C ...

(c. 1200 – 1000 BCE) are among the earliest testimonies of Indian music, but they contain no theory properly speaking. The Natya Shastra

The ''Nāṭya Śāstra'' (, ''Nāṭyaśāstra'') is a Sanskrit treatise on the performing arts. The text is attributed to sage Bharata Muni, and its first complete compilation is dated to between 200 BCE and 200 CE, but estimates vary ...

, written between 200 BCE to 200 CE, discusses intervals (''Śrutis''), scales (''Grāmas''), consonances and dissonances, classes of melodic structure (''Mūrchanās'', modes?), melodic types (''Jātis''), instruments, etc.

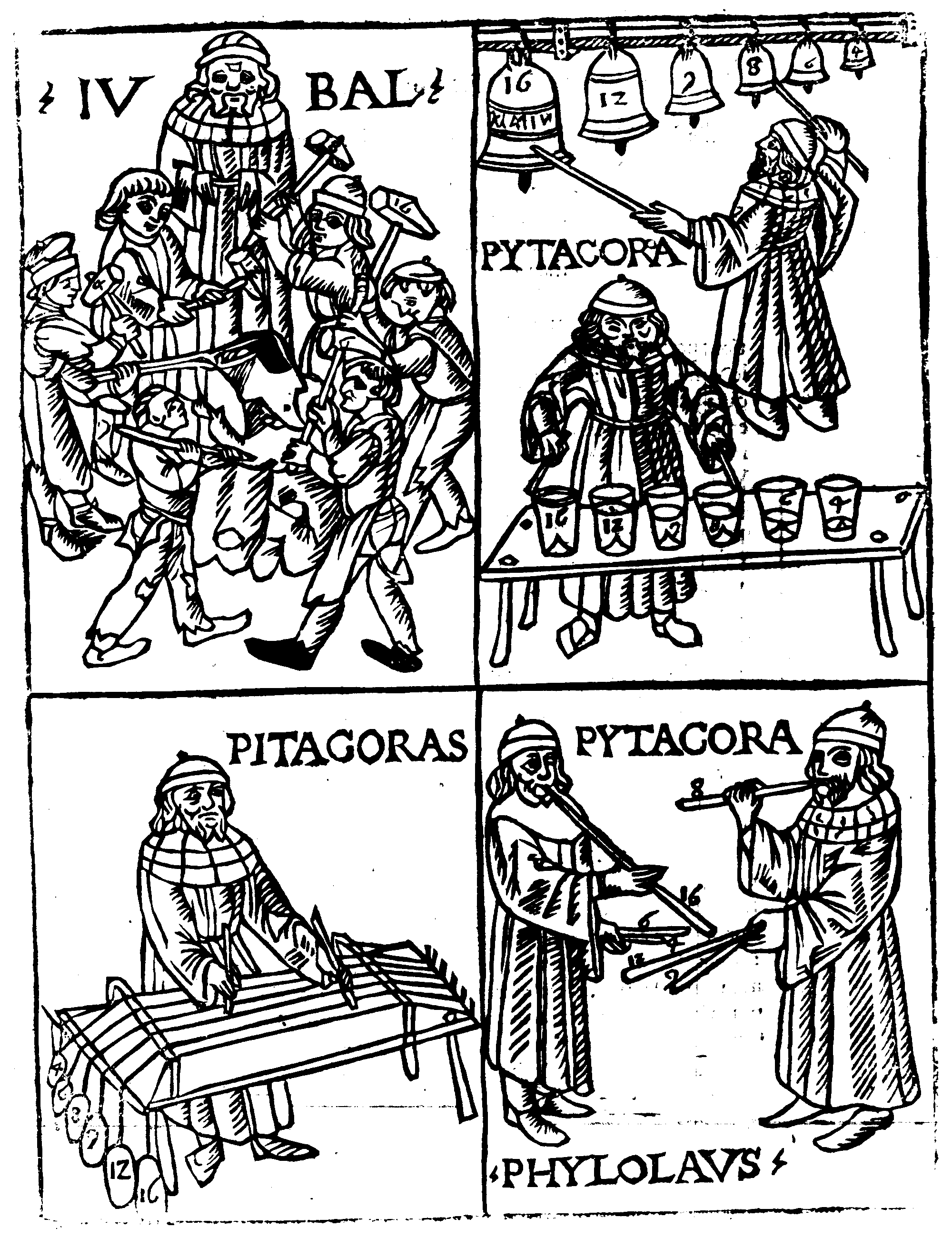

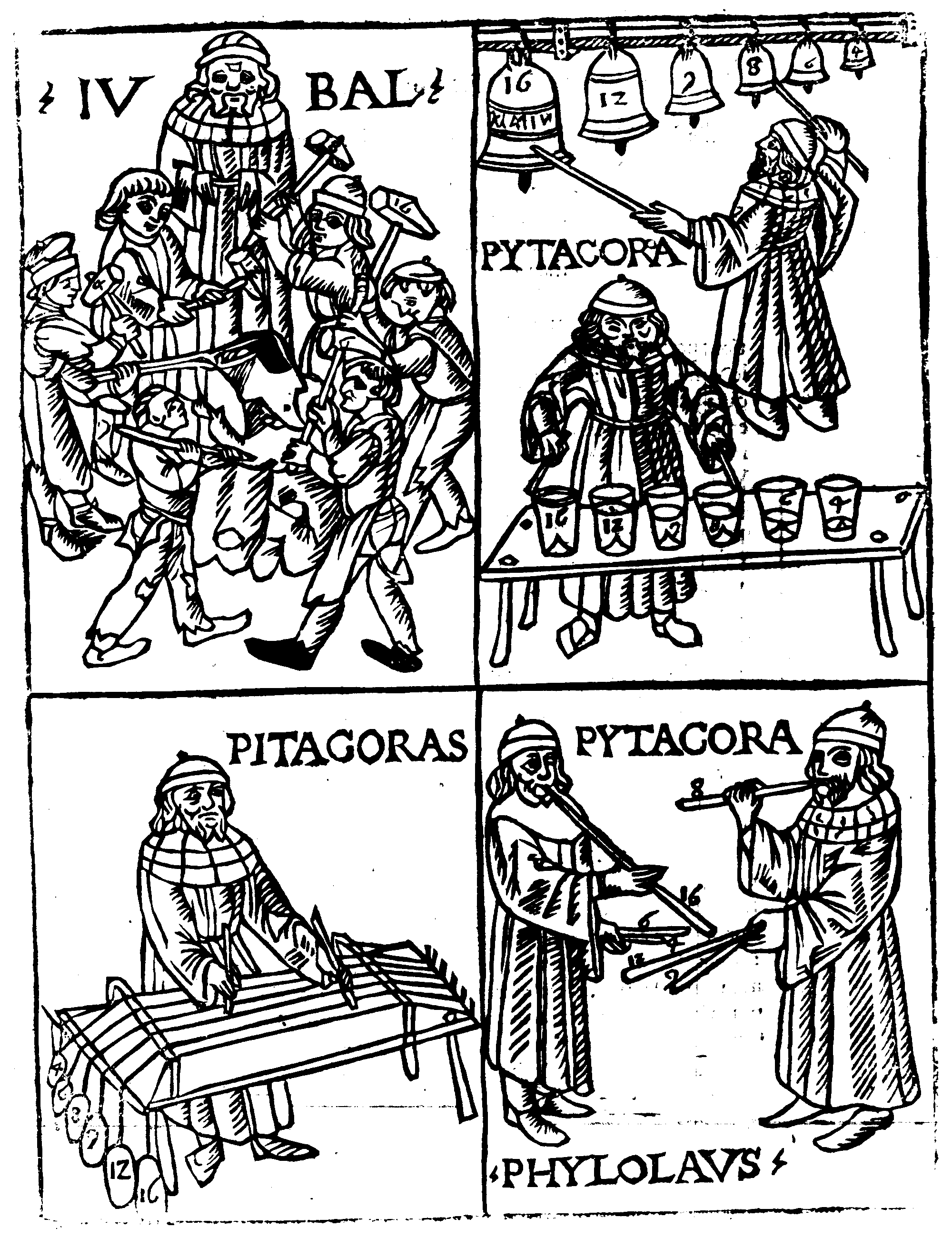

Greece

Early preserved Greek writings on music theory include two types of works: * technical manuals describing the Greek musical system including notation, scales, consonance and dissonance, rhythm, and types of musical compositions * treatises on the way in which music reveals universal patterns of order leading to the highest levels of knowledge and understanding. Several names of theorists are known before these works, includingPythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samos, Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionians, Ionian Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher and the eponymou ...

(c. 570 – c. 495 BCE), Philolaus

Philolaus (; grc, Φιλόλαος, ''Philólaos''; ) was a Greek Pythagorean and pre-Socratic philosopher. He was born in a Greek colony in Italy and migrated to Greece. Philolaus has been called one of three most prominent figures in the Pytha ...

(c. 470 – c. 385 BCE), Archytas

Archytas (; el, Ἀρχύτας; 435/410–360/350 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosopher, mathematician, music theorist, astronomer, statesman, and strategist. He was a scientist of the Pythagorean school and famous for being the reputed founder ...

(428–347 BCE), and others.

Works of the first type (technical manuals) include

* Anonymous (erroneously attributed to Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Wikt:Εὐκλείδης, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the ''Euclid's Elements, Elements'' trea ...

) ''Division of the Canon'', Κατατομή κανόνος, 4th–3rd century BCE.

* Theon of Smyrna

Theon of Smyrna ( el, Θέων ὁ Σμυρναῖος ''Theon ho Smyrnaios'', ''gen.'' Θέωνος ''Theonos''; fl. 100 CE) was a Greek philosopher and mathematician, whose works were strongly influenced by the Pythagorean school of thought. His ...

, ''On Mathematics Useful for the Understanding of Plato'', Τωv κατά τό μαθηματικόν χρησίμων είς τήν Πλάτωνος άνάγνωσις, 115–140 CE.

* Nicomachus of Gerasa

Nicomachus of Gerasa ( grc-gre, Νικόμαχος; c. 60 – c. 120 AD) was an important ancient mathematician and music theorist, best known for his works ''Introduction to Arithmetic'' and ''Manual of Harmonics'' in Greek. He was born in ...

, ''Manual of Harmonics'', Άρμονικόν έγχειρίδιον, 100–150 CE

* Cleonides Cleonides ( el, Κλεονείδης) is the author of a Greek treatise on music theory titled Εἰσαγωγὴ ἁρμονική ''Eisagōgē harmonikē'' (Introduction to Harmonics). The date of the treatise, based on internal evidence, can be e ...

, ''Introduction to Harmonics'', Είσαγωγή άρμονική, 2nd century CE.

* Gaudentius, ''Harmonic Introduction'', Άρμονική είσαγωγή, 3d or 4th century CE.

* Bacchius Geron, ''Introduction to the Art of Music'', Είσαγωγή τέχνης μουσικής, 4th century CE or later.

* Alypius, ''Introduction to Music'', Είσαγωγή μουσική, 4th–5th century CE.

More philosophical treatises of the second type include

* Aristoxenus

Aristoxenus of Tarentum ( el, Ἀριστόξενος ὁ Ταραντῖνος; born 375, fl. 335 BC) was a Greek Peripatetic philosopher, and a pupil of Aristotle. Most of his writings, which dealt with philosophy, ethics and music, have been ...

, ''Harmonic Elements'', Άρμονικά στοιχεία, 375/360 – after 320 BCE.

* Aristoxenus

Aristoxenus of Tarentum ( el, Ἀριστόξενος ὁ Ταραντῖνος; born 375, fl. 335 BC) was a Greek Peripatetic philosopher, and a pupil of Aristotle. Most of his writings, which dealt with philosophy, ethics and music, have been ...

, ''Rhythmic Elements'', Ρυθμικά στοιχεία.

* Claudius Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

, ''Harmonics'', Άρμονικά, 127–148 CE.

* Porphyrius, ''On Ptolemy's Harmonics'', Είς τά άρμονικά Πτολεμαίον ύπόμνημα, 232/3–c. 305 CE.

Post-classical

China

Thepipa

The pipa, pípá, or p'i-p'a () is a traditional Chinese musical instrument, belonging to the plucked category of instruments. Sometimes called the "Chinese lute", the instrument has a pear-shaped wooden body with a varying number of frets rang ...

instrument carried with it a theory of musical modes that subsequently led to the Sui and Tang theory of 84 musical modes.

Arabic countries / Persian countries

Medieval Arabic music theorists include: * Abū Yūsuf Ya'qūbal-Kindi

Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn ʼIsḥāq aṣ-Ṣabbāḥ al-Kindī (; ar, أبو يوسف يعقوب بن إسحاق الصبّاح الكندي; la, Alkindus; c. 801–873 AD) was an Arab Muslim philosopher, polymath, mathematician, physician ...

(† Bagdad, 873 CE), who uses the first twelve letters of the alphabet to describe the twelve frets on five strings of the oud

, image=File:oud2.jpg

, image_capt=Syrian oud made by Abdo Nahat in 1921

, background=

, classification=

* String instruments

*Necked bowl lutes

, hornbostel_sachs=321.321-6

, hornbostel_sachs_desc=Composite chordophone sounded with a plectrum

, ...

, producing a chromatic scale of 25 degrees.

* aḥyā ibnal- Munajjim (Baghdad, 856–912), author of ''Risāla fī al-mūsīqī'' ("Treatise on music", MS GB-Lbl Oriental 2361) which describes a Pythagorean tuning

Pythagorean tuning is a system of musical tuning in which the frequency ratios of all intervals are based on the ratio 3:2.Bruce Benward and Marilyn Nadine Saker (2003). ''Music: In Theory and Practice'', seventh edition, 2 vols. (Boston: Mc ...

of the oud

, image=File:oud2.jpg

, image_capt=Syrian oud made by Abdo Nahat in 1921

, background=

, classification=

* String instruments

*Necked bowl lutes

, hornbostel_sachs=321.321-6

, hornbostel_sachs_desc=Composite chordophone sounded with a plectrum

, ...

and a system of eight modes perhaps inspired by Ishaq al-Mawsili

Ishaq al-Mawsili ( ar, إسحاق الموصلي; 767/772 – March 850) was an Arab musician of Persian origin active as a composer, singer, music theorist and writer on music. The leading musician of his time in the Abbasid Caliphate, he served ...

(767–850).

* Abū n-Nașr Muḥammad al-Fārābi (Persia, 872? – Damas, 950 or 951 CE), author of ''Kitab al-Musiqa al-Kabir

''Kitab al-Musiqa al-Kabir'' ( ar, كتاب الموسيقى الكبير, en, the Great Book of Music) is a treatise on music in east by the medieval philosopher al-Farabi (872-950/951). The work prescribes different aspects of music such as ma ...

'' ("The Great Book of Music").

* 'Ali ibn al-Husayn ul-Isfahānī (897–967), known as Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani

Ali ibn al-Husayn al-Iṣfahānī ( ar, أبو الفرج الأصفهاني), also known as Abul-Faraj, (full form: Abū al-Faraj ʿAlī ibn al-Ḥusayn ibn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn al-Ḥaytham al-Umawī al-Iṣfahānī) (284–356 AH / 897 ...

, author of ''Kitāb al-Aghānī'' ("The Book of Songs").

* Abū 'Alī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd-Allāh ibn Sīnā, known as Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic G ...

(c. 980 – 1037), whose contribution to music theory consists mainly in Chapter 12 of the section on mathematics of his ''Kitab Al-Shifa'' ("The Book of Healing

''The Book of Healing'' (; ; also known as ) is a scientific and philosophical encyclopedia written by Abu Ali ibn Sīna (aka Avicenna) from medieval Persia, near Bukhara in Maverounnahr. He most likely began to compose the book in 1014, comp ...

").

* al-Ḥasan ibn Aḥmad ibn 'Ali al-Kātib, author of Kamāl adab al Ghinā' ("The Perfection of Musical Knowledge"), copied in 1225 (Istanbul, Topkapi Museum, Ms 1727).

* Safi al-Din al-Urmawi

Safi al-Din al-Urmawi al-Baghdadi ( fa, صفی الدین اورموی) or Safi al-Din Abd al-Mu'min ibn Yusuf ibn al-Fakhir al-Urmawi al-Baghdadi (born c. 1216 AD in Urmia, died in 1294 AD in Baghdad) was a renowned musician and writer on the ...

(1216–1294 CE), author of the ''Kitabu al-Adwār'' ("Treatise of musical cycles") and ''ar-Risālah aš-Šarafiyyah'' ("Epistle to Šaraf").

* Mubārak Šāh, commentator of Safi al-Din's ''Kitāb al-Adwār'' (British Museum, Ms 823).

* Anon. LXI, Anonymous commentary on Safi al-Din's ''Kitāb al-Adwār''.

* Shams al-dῑn al-Saydᾱwῑ Al-Dhahabῑ (14th century CE (?)), music theorist. Author of ''Urjῡza fi'l-mῡsῑqᾱ'' ("A Didactic Poem on Music").

Europe

The Latin treatise ''De institutione musica'' by the Roman philosopherBoethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480 – 524 AD), was a Roman senator, consul, ''magister officiorum'', historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the tr ...

(written c. 500, translated as ''Fundamentals of Music'') was a touchstone for other writings on music in medieval Europe. Boethius represented Classical authority on music during the Middle Ages, as the Greek writings on which he based his work were not read or translated by later Europeans until the 15th century. This treatise carefully maintains distance from the actual practice of music, focusing mostly on the mathematical proportions involved in tuning systems and on the moral character of particular modes. Several centuries later, treatises began to appear which dealt with the actual composition of pieces of music in the plainchant

Plainsong or plainchant (calque from the French ''plain-chant''; la, cantus planus) is a body of chants used in the liturgies of the Western Church. When referring to the term plainsong, it is those sacred pieces that are composed in Latin text. ...

tradition. At the end of the ninth century, Hucbald

Hucbald ( – 20 June 930; also Hucbaldus or Hubaldus) was a Benedictine monk active as a music theorist, poet, composer, teacher, and hagiographer. He was long associated with Saint-Amand Abbey, so is often known as Hucbald of St Amand. Deeply i ...

worked towards more precise pitch notation for the neume

A neume (; sometimes spelled neum) is the basic element of Western and Eastern systems of musical notation prior to the invention of five-line staff notation.

The earliest neumes were inflective marks that indicated the general shape but not ne ...

s used to record plainchant.

Guido d'Arezzo

Guido of Arezzo ( it, Guido d'Arezzo; – after 1033) was an Italian music theorist and pedagogue of High medieval music. A Benedictine monk, he is regarded as the inventor—or by some, developer—of the modern staff notation that had a mas ...

' wrote in 1028 a letter to Michael of Pomposa, entitled ''Epistola de ignoto cantu'', in which he introduced the practice of using syllables to describe notes and intervals. This was the source of the hexachordal solmization

Solmization is a system of attributing a distinct syllable to each note of a musical scale. Various forms of solmization are in use and have been used throughout the world, but solfège is the most common convention in countries of Western cultur ...

that was to be used until the end of the Middle Ages. Guido also wrote about emotional qualities of the modes, the phrase structure of plainchant, the temporal meaning of the neumes, etc.; his chapters on polyphony "come closer to describing and illustrating real music than any previous account" in the Western tradition.

During the thirteenth century, a new rhythm system called mensural notation

Mensural notation is the musical notation system used for European vocal polyphonic music from the later part of the 13th century until about 1600. The term "mensural" refers to the ability of this system to describe precisely measured rhythm ...

grew out of an earlier, more limited method of notating rhythms in terms of fixed repetitive patterns, the so-called rhythmic modes, which were developed in France around 1200. An early form of mensural notation was first described and codified in the treatise ''Ars cantus mensurabilis'' ("The art of measured chant") by Franco of Cologne

Franco of Cologne (; also Franco of Paris) was a German music theorist and possibly a composer. He was one of the most influential theorists of the Late Middle Ages, and was the first to propose an idea which was to transform musical notation per ...

(c. 1280). Mensural notation used different note shapes to specify different durations, allowing scribes to capture rhythms which varied instead of repeating the same fixed pattern; it is a proportional notation, in the sense that each note value is equal to two or three times the shorter value, or half or a third of the longer value. This same notation, transformed through various extensions and improvements during the Renaissance, forms the basis for rhythmic notation in European classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical music, as the term "classical music" also ...

today.

Modern

Middle Eastern and Central Asian countries

* Bᾱqiyᾱ Nᾱyinῑ (Uzbekistan, 17th century CE), Uzbek author and music theorist. Author of ''Zamzama e wahdat-i-mῡsῑqῑ'' ("The Chanting of Unity in Music"). * Baron Francois Rodolphe d'Erlanger (Tunis, Tunisia, 1910–1932 CE), French musicologist. Author of ''La musique arabe'' and ''Ta'rῑkh al-mῡsῑqᾱ al-arabiyya wa-usῡluha wa-tatawwurᾱtuha'' ("A History of Arabian Music, its principles and its Development") D'Erlanger divulges that the Arabic music scale is derived from the Greek music scale, and that Arabic music is connected to certain features of Arabic culture, such as astrology.Europe

* Renaissance * Baroque * 1750–1900 ** As Western musical influence spread throughout the world in the 1800s, musicians adopted Western theory as an international standard—but other theoretical traditions in both textual and oral traditions remain in use. For example, the long and rich musical traditions unique to ancient and current cultures of Africa are primarily oral, but describe specific forms, genres, performance practices, tunings, and other aspects of music theory. **Sacred harp

Sacred Harp singing is a tradition of sacred choral music that originated in New England and was later perpetuated and carried on in the American South. The name is derived from ''The Sacred Harp'', a ubiquitous and historically important tune ...

music uses a different kind of scale and theory in practice. The music focuses on the solfege "fa, sol, la" on the music scale. Sacred Harp also employs a different notation involving "shape notes", or notes that are shaped to correspond to a certain solfege syllable on the music scale. Sacred Harp music and its music theory originated with Reverend Thomas Symmes in 1720, where he developed a system for "singing by note" to help his church members with note accuracy.

Contemporary

Fundamentals of music

Music is composed ofaural

Hearing, or auditory perception, is the ability to perceive sounds through an organ, such as an ear, by detecting vibrations as periodic changes in the pressure of a surrounding medium. The academic field concerned with hearing is auditory ...

phenomena; "music theory" considers how those phenomena apply in music. Music theory considers melody, rhythm, counterpoint, harmony, form, tonal systems, scales, tuning, intervals, consonance, dissonance, durational proportions, the acoustics of pitch systems, composition, performance, orchestration, ornamentation, improvisation, electronic sound production, etc.

Pitch

Pitch is the lowness or highness of a tone, for example the difference between

Pitch is the lowness or highness of a tone, for example the difference between middle C

C or Do is the first note and semitone of the C major scale, the third note of the A minor scale (the relative minor of C major), and the fourth note (G, A, B, C) of the Guidonian hand, commonly pitched around 261.63 Hz. The actual frequen ...

and a higher C. The frequency of the sound waves producing a pitch can be measured precisely, but the perception of pitch is more complex because single notes from natural sources are usually a complex mix of many frequencies. Accordingly, theorists often describe pitch as a subjective sensation rather than an objective measurement of sound.

Specific frequencies are often assigned letter names. Today most orchestras assign concert A

Concert pitch is the pitch (music), pitch reference to which a group of musical instruments are musical tuning, tuned for a performance. Concert pitch may vary from musical ensemble, ensemble to ensemble, and has varied widely over music history. ...

(the A above middle C

C or Do is the first note and semitone of the C major scale, the third note of the A minor scale (the relative minor of C major), and the fourth note (G, A, B, C) of the Guidonian hand, commonly pitched around 261.63 Hz. The actual frequen ...

on the piano) to the frequency of 440 Hz. This assignment is somewhat arbitrary; for example, in 1859 France, the same A was tuned to 435 Hz. Such differences can have a noticeable effect on the timbre of instruments and other phenomena. Thus, in historically informed performance

Historically informed performance (also referred to as period performance, authentic performance, or HIP) is an approach to the performance of Western classical music, classical music, which aims to be faithful to the approach, manner and style of ...

of older music, tuning is often set to match the tuning used in the period when it was written. Additionally, many cultures do not attempt to standardize pitch, often considering that it should be allowed to vary depending on genre, style, mood, etc.

The difference in pitch between two notes is called an interval. The most basic interval is the unison

In music, unison is two or more musical parts that sound either the same pitch or pitches separated by intervals of one or more octaves, usually at the same time. ''Rhythmic unison'' is another term for homorhythm.

Definition

Unison or per ...

, which is simply two notes of the same pitch. The octave

In music, an octave ( la, octavus: eighth) or perfect octave (sometimes called the diapason) is the interval between one musical pitch and another with double its frequency. The octave relationship is a natural phenomenon that has been refer ...

interval is two pitches that are either double or half the frequency of one another. The unique characteristics of octaves gave rise to the concept of pitch class

In music, a pitch class (p.c. or pc) is a set of all pitches that are a whole number of octaves apart; for example, the pitch class C consists of the Cs in all octaves. "The pitch class C stands for all possible Cs, in whatever octave positio ...

: pitches of the same letter name that occur in different octaves may be grouped into a single "class" by ignoring the difference in octave. For example, a high C and a low C are members of the same pitch class—the class that contains all C's.

Musical tuning

In music, there are two common meanings for tuning:

* Tuning practice, the act of tuning an instrument or voice.

* Tuning systems, the various systems of pitches used to tune an instrument, and their theoretical bases.

Tuning practice

Tun ...

systems, or temperaments, determine the precise size of intervals. Tuning systems vary widely within and between world cultures. In Western culture

Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions">human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Cle ...

, there have long been several competing tuning systems, all with different qualities. Internationally, the system known as equal temperament

An equal temperament is a musical temperament or tuning system, which approximates just intervals by dividing an octave (or other interval) into equal steps. This means the ratio of the frequencies of any adjacent pair of notes is the same, wh ...

is most commonly used today because it is considered the most satisfactory compromise that allows instruments of fixed tuning (e.g. the piano) to sound acceptably in tune in all keys.

Scales and modes

Notes can be arranged in a variety of scales and

Notes can be arranged in a variety of scales and modes

Mode ( la, modus meaning "manner, tune, measure, due measure, rhythm, melody") may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* '' MO''D''E (magazine)'', a defunct U.S. women's fashion magazine

* ''Mode'' magazine, a fictional fashion magazine which is ...

. Western music theory generally divides the octave into a series of twelve pitches, called a chromatic scale

The chromatic scale (or twelve-tone scale) is a set of twelve pitches (more completely, pitch classes) used in tonal music, with notes separated by the interval of a semitone. Chromatic instruments, such as the piano, are made to produce the ...

, within which the interval between adjacent tones is called a half step, or semitone

A semitone, also called a half step or a half tone, is the smallest musical interval commonly used in Western tonal music, and it is considered the most dissonant when sounded harmonically.

It is defined as the interval between two adjacent no ...

. Selecting tones from this set of 12 and arranging them in patterns of semitones and whole tones creates other scales.

The most commonly encountered scales are the seven-toned major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

, the harmonic minor

In music theory, the minor scale is three scale patterns – the natural minor scale (or Aeolian mode), the harmonic minor scale, and the melodic minor scale (ascending or descending) – rather than just two as with the major scale, which also ...

, the melodic minor

In music theory, the minor scale is three scale patterns – the natural minor scale (or Aeolian mode), the harmonic minor scale, and the melodic minor scale (ascending or descending) – rather than just two as with the major scale, which al ...

, and the natural minor

In music theory, the minor scale is three scale patterns – the natural minor scale (or Aeolian mode), the harmonic minor scale, and the melodic minor scale (ascending or descending) – rather than just two as with the major scale, which also ...

. Other examples of scales are the octatonic scale

An octatonic scale is any eight-note musical scale. However, the term most often refers to the symmetric scale composed of alternating whole and half steps, as shown at right. In classical theory (in contrast to jazz theory), this symmetrical ...

and the pentatonic

A pentatonic scale is a musical scale with five notes per octave, in contrast to the heptatonic scale, which has seven notes per octave (such as the major scale and minor scale).

Pentatonic scales were developed independently by many ancie ...

or five-tone scale, which is common in folk music

Folk music is a music genre that includes traditional folk music and the contemporary genre that evolved from the former during the 20th-century folk revival. Some types of folk music may be called world music. Traditional folk music has b ...

and blues

Blues is a music genre and musical form which originated in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s. Blues incorporated spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts, chants, and rhymed simple narrative ballads from the Afr ...

. Non-Western cultures often use scales that do not correspond with an equally divided twelve-tone division of the octave. For example, classical Ottoman, Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

, Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

and Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

musical systems often make use of multiples of quarter tones (half the size of a semitone, as the name indicates), for instance in 'neutral' seconds (three quarter tones) or 'neutral' thirds (seven quarter tones)—they do not normally use the quarter tone itself as a direct interval.

In traditional Western notation, the scale used for a composition is usually indicated by a key signature

In Western musical notation, a key signature is a set of sharp (), flat (), or rarely, natural () symbols placed on the staff at the beginning of a section of music. The initial key signature in a piece is placed immediately after the clef at ...

at the beginning to designate the pitches that make up that scale. As the music progresses, the pitches used may change and introduce a different scale. Music can be transposed

In linear algebra, the transpose of a matrix is an operator which flips a matrix over its diagonal;

that is, it switches the row and column indices of the matrix by producing another matrix, often denoted by (among other notations).

The tr ...

from one scale to another for various purposes, often to accommodate the range of a vocalist. Such transposition raises or lowers the overall pitch range, but preserves the intervallic relationships of the original scale. For example, transposition from the key of C major to D major raises all pitches of the scale of C major equally by a whole tone

In Western music theory, a major second (sometimes also called whole tone or a whole step) is a second spanning two semitones (). A second is a musical interval encompassing two adjacent staff positions (see Interval number for more deta ...

. Since the interval relationships remain unchanged, transposition may be unnoticed by a listener, however other qualities may change noticeably because transposition changes the relationship of the overall pitch range

Range may refer to:

Geography

* Range (geographic), a chain of hills or mountains; a somewhat linear, complex mountainous or hilly area (cordillera, sierra)

** Mountain range, a group of mountains bordered by lowlands

* Range, a term used to i ...

compared to the range of the instruments or voices that perform the music. This often affects the music's overall sound, as well as having technical implications for the performers.

The interrelationship of the keys most commonly used in Western tonal music is conveniently shown by the circle of fifths

In music theory, the circle of fifths is a way of organizing the 12 chromatic pitches as a sequence of perfect fifths. (This is strictly true in the standard 12-tone equal temperament system — using a different system requires one interval ...

. Unique key signatures are also sometimes devised for a particular composition. During the Baroque period, emotional associations with specific keys, known as the doctrine of the affections

The doctrine of the affections, also known as the ''doctrine of affects'', ''doctrine of the passions'', ''theory of the affects'', or by the German term Affektenlehre (after the German ''Affekt''; plural ''Affekte'') was a theory in the aesthe ...

, were an important topic in music theory, but the unique tonal colorings of keys that gave rise to that doctrine were largely erased with the adoption of equal temperament. However, many musicians continue to feel that certain keys are more appropriate to certain emotions than others. Indian classical music

Indian classical music is the classical music of the Indian subcontinent. It has two major traditions: the North Indian classical music known as '' Hindustani'' and the South Indian expression known as '' Carnatic''. These traditions were not ...

theory continues to strongly associate keys with emotional states, times of day, and other extra-musical concepts and notably, does not employ equal temperament.

Consonance and dissonance

Consonance and dissonance

In music, consonance and dissonance are categorizations of simultaneous or successive Sound, sounds. Within the Western tradition, some listeners associate consonance with sweetness, pleasantness, and acceptability, and dissonance with harshness ...

are subjective qualities of the sonority of intervals that vary widely in different cultures and over the ages. Consonance (or concord) is the quality of an interval or chord that seems stable and complete in itself. Dissonance (or discord) is the opposite in that it feels incomplete and "wants to" resolve to a consonant interval. Dissonant intervals seem to clash. Consonant intervals seem to sound comfortable together. Commonly, perfect fourths, fifths, and octaves and all major and minor thirds and sixths are considered consonant. All others are dissonant to a greater or lesser degree.

Context and many other aspects can affect apparent dissonance and consonance. For example, in a Debussy prelude, a major second may sound stable and consonant, while the same interval may sound dissonant in a Bach fugue. In the Common practice era, the perfect fourth is considered dissonant when not supported by a lower third or fifth. Since the early 20th century, Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was as ...

's concept of "emancipated" dissonance, in which traditionally dissonant intervals can be treated as "higher," more remote consonances, has become more widely accepted.

Rhythm

Meter

The metre (British spelling) or meter (American spelling; see spelling differences) (from the French unit , from the Greek noun , "measure"), symbol m, is the primary unit of length in the International System of Units (SI), though its prefi ...

measures music in regular pulse groupings, called measures or bars. The time signature

The time signature (also known as meter signature, metre signature, or measure signature) is a notational convention used in Western musical notation to specify how many beats (pulses) are contained in each measure (bar), and which note value ...

or meter signature specifies how many beats are in a measure, and which value of written note is counted or felt as a single beat.

Through increased stress, or variations in duration or articulation, particular tones may be accented. There are conventions in most musical traditions for regular and hierarchical accentuation of beats to reinforce a given meter. Syncopated

In music, syncopation is a variety of rhythms played together to make a piece of music, making part or all of a tune or piece of music off-beat. More simply, syncopation is "a disturbance or interruption of the regular flow of rhythm": a "place ...

rhythms contradict those conventions by accenting unexpected parts of the beat. Playing simultaneous rhythms in more than one time signature is called polyrhythm

Polyrhythm is the simultaneous use of two or more rhythms that are not readily perceived as deriving from one another, or as simple manifestations of the same meter. The rhythmic layers may be the basis of an entire piece of music (cross-rhyth ...

.

In recent years, rhythm and meter have become an important area of research among music scholars. The most highly cited of these recent scholars are Maury Yeston

Maury Yeston (born October 23, 1945) is an American composer, lyricist and music theorist.

He is known as the initiator of new Broadway musicals and writing their music and lyrics, as well as a classical orchestral and ballet composer, Yale Uni ...

, Fred Lerdahl

Alfred Whitford (Fred) Lerdahl (born March 10, 1943, in Madison, Wisconsin) is the Fritz Reiner Professor Emeritus of Musical Composition at Columbia University, and a composer and music theorist best known for his work on musical grammar and cogn ...

and Ray Jackendoff

Ray Jackendoff (born January 23, 1945) is an American linguist. He is professor of philosophy, Seth Merrin Chair in the Humanities and, with Daniel Dennett, co-director of the Center for Cognitive Studies at Tufts University. He has always str ...

, Jonathan Kramer

Jonathan Donald Kramer (December 7, 1942, Hartford, Connecticut – June 3, 2004, New York City) was an American composer and music theorist.

Biography

Kramer received his B.A. magna cum laude from Harvard University (1965) and his MA and ...

, and Justin London.

Melody

melody

A melody (from Greek language, Greek μελῳδία, ''melōidía'', "singing, chanting"), also tune, voice or line, is a Linearity#Music, linear succession of musical tones that the listener perceives as a single entity. In its most liter ...

is a series of tones ''perceived as an entity'', sounding in succession that typically move toward a climax of tension then resolve to a state of rest. Because melody is such a prominent aspect in so much music, its construction and other qualities are a primary interest of music theory.

The basic elements of melody are pitch, duration, rhythm, and tempo. The tones of a melody are usually drawn from pitch systems such as scales

Scale or scales may refer to:

Mathematics

* Scale (descriptive set theory), an object defined on a set of points

* Scale (ratio), the ratio of a linear dimension of a model to the corresponding dimension of the original

* Scale factor, a number w ...

or modes

Mode ( la, modus meaning "manner, tune, measure, due measure, rhythm, melody") may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* '' MO''D''E (magazine)'', a defunct U.S. women's fashion magazine

* ''Mode'' magazine, a fictional fashion magazine which is ...

. Melody may consist, to increasing degree, of the figure, motive, semi-phrase, antecedent and consequent phrase, and period or sentence. The period may be considered the complete melody, however some examples combine two periods, or use other combinations of constituents to create larger form melodies.

Chord

harmonic

A harmonic is a wave with a frequency that is a positive integer multiple of the ''fundamental frequency'', the frequency of the original periodic signal, such as a sinusoidal wave. The original signal is also called the ''1st harmonic'', the ...

set of three or more note

Note, notes, or NOTE may refer to:

Music and entertainment

* Musical note, a pitched sound (or a symbol for a sound) in music

* ''Notes'' (album), a 1987 album by Paul Bley and Paul Motian

* ''Notes'', a common (yet unofficial) shortened version ...

s that is heard as if sounding simultaneously

Simultaneity may refer to:

* Relativity of simultaneity, a concept in special relativity.

* Simultaneity (music), more than one complete musical texture occurring at the same time, rather than in succession

* Simultaneity, a concept in Endogene ...

. These need not actually be played together: arpeggio

A broken chord is a chord broken into a sequence of notes. A broken chord may repeat some of the notes from the chord and span one or more octaves.

An arpeggio () is a type of broken chord, in which the notes that compose a chord are played ...

s and broken chords may, for many practical and theoretical purposes, constitute chords. Chords and sequences of chords are frequently used in modern Western, West African, and Oceanian music, whereas they are absent from the music of many other parts of the world.

The most frequently encountered chords are triads, so called because they consist of three distinct notes: further notes may be added to give seventh chord

A seventh chord is a chord consisting of a triad plus a note forming an interval of a seventh above the chord's root. When not otherwise specified, a "seventh chord" usually means a dominant seventh chord: a major triad together with a minor ...

s, extended chord

In music, extended chords are certain chords (built from thirds) or triads with notes ''extended'', or added, beyond the seventh. Ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth chords are extended chords. The thirteenth is the farthest extension diatonical ...

s, or added tone chord

An added tone chord, or added note chord, is a non- tertian chord composed of a triad and an extra "added" note. Any tone that is not a seventh factor is commonly categorized as an added tone. It can be outside the tertian sequence of ascendin ...

s. The most common chords are the ''major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

'' and ''minor

Minor may refer to:

* Minor (law), a person under the age of certain legal activities.

** A person who has not reached the age of majority

* Academic minor, a secondary field of study in undergraduate education

Music theory

*Minor chord

** Barb ...

triads'' and then the '' augmented'' and '' diminished triads''. The descriptions ''major'', ''minor'', ''augmented'', and ''diminished'' are sometimes referred to collectively as chordal ''quality''. Chords are also commonly classed by their root

In vascular plants, the roots are the organs of a plant that are modified to provide anchorage for the plant and take in water and nutrients into the plant body, which allows plants to grow taller and faster. They are most often below the sur ...

note—so, for instance, the chord C major may be described as a triad of major quality built on the note C. Chords may also be classified by inversion

Inversion or inversions may refer to:

Arts

* , a French gay magazine (1924/1925)

* ''Inversion'' (artwork), a 2005 temporary sculpture in Houston, Texas

* Inversion (music), a term with various meanings in music theory and musical set theory

* ...

, the order in which the notes are stacked.